By Rumilda Canete-Straub, Josepa Miquel-Florensa, Stephane Straub & Karine Van der Straeten

“The conventional argument in favor of open-list systems as a remedy against corruption is that voters can express their preferences over the individual candidates on this list.”

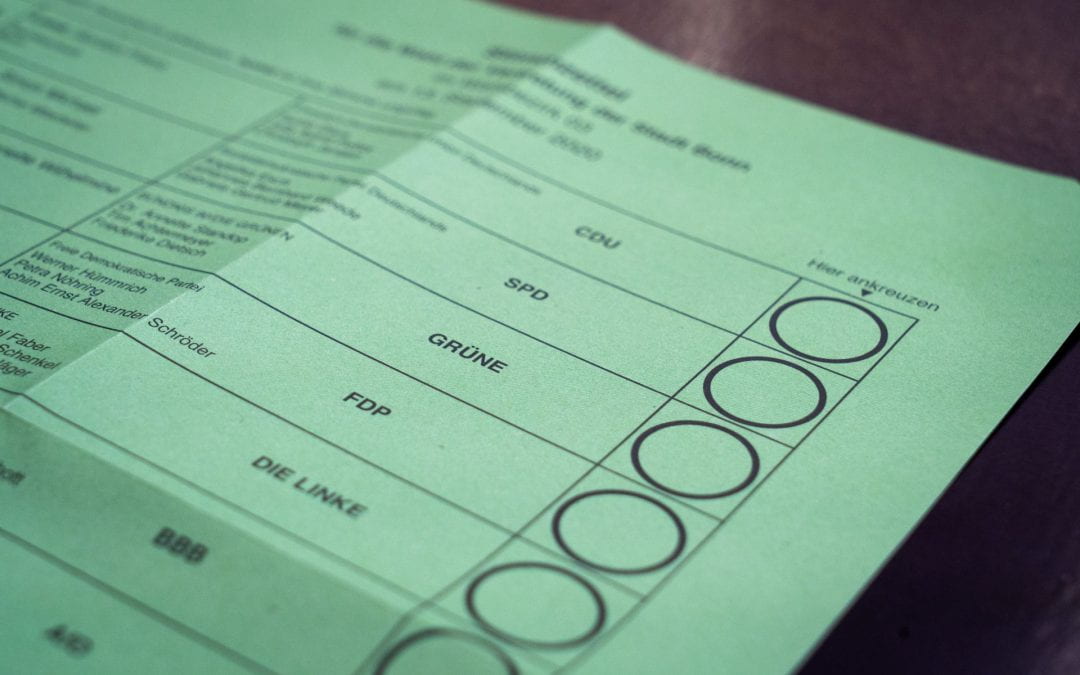

Although many people hope and expect that regular elections will help reduce corruption, this is not always the case: In many democracies, voters elect and reelect corrupt politicians. Why is this? Scholars have suggested that the efficacy of electoral democracy in reducing corruption depends on specific features of the electoral system, and the information available to voters. With respect to the electoral system, a common view is that electoral rules that give voters more formal control over individual candidates—such as primaries in majoritarian systems or open lists rather than closed lists in proportional representation (PR) systems—are more effective in reducing corruption. With respect to information, the conventional wisdom holds that providing voters with more information should help them identify corrupt politicians, thus increasing the chances that those politicians will be punished at the ballot box.

In our recent article, we present findings that challenge both aspects of this conventional wisdom. We focus on the comparison between closed-list PR system (in which voters vote only for a party, with the individual candidates elected depending on their position on the party’s list) and an open-list PR system in which voters can vote for any number of candidates on the list, without any constraint.

Our analysis highlights a neglected countervailing effect of open-list systems as a tool against corruption. The conventional argument in favor of open-list systems as a remedy against corruption is that voters can express their preferences over the individual candidates on this list. This argument implicitly assumes that voters vote for the same parties under both systems. But that is not necessarily so. In fact, opening the lists tends to benefit the party whose list includes candidates over which voters have strong preferences, because the ability to favor specific candidates is more valuable to a voter for lists featuring not only candidates that the voters strongly like but also candidates that the voters strongly dislike. That means, in turn, that opening the lists will also be more beneficial for lists whose candidates are well known to the voters. And this implies that moving from a closed-list system to an open-list system is likely to increase the vote shares of the incumbent parties, because incumbent parties are generally better known by voters and their candidates are likely to generate stronger feelings.

This means that switching from a closed list to an open list may cause at least some voters to switch from voting for the opposition party to voting for the incumbent party, because those voters have only a mild preference for the opposition to the incumbent party overall, but have very strong feelings about which incumbent politicians they like (or don’t like). That might hurt some individual corrupt incumbents, but it might increase the incumbent party’s overall vote share, leading to the incumbent party winning more seats. And if the incumbent party is more corrupt, this effect could reduce or even override the corruption-reducing effect of opening the party lists.

Skeptics might question whether this theoretical possibility manifests in the real world—or manifests sufficiently to matter. We can’t directly test this hypothesis by randomly changing real electoral systems, so we instead conducted a survey experiment in Paraguay. (Paraguay is an institutionally weak democracy consistently ranked among the most corrupt in Latin America. It has long been characterized by a strong two-party system, which currently uses a closed-list PR system to elect its Senators, though there is an ongoing debate about a potential electoral reform to open the lists, which reform proponents argue will help reduce corruption.) We presented our survey respondents with two hypothetical elections, one under closed-list PR and one under open-list PR, featuring the same party lists as in the previous senatorial election. We found that the incumbent party—which is widely perceived as corrupt—received a substantially larger vote share (about 6 or 7 percentage points) under the open-list system, and this increase came mainly at the expense of smaller parties with candidates less well-known to the public.

Additionally, before the respondents were invited to vote in the hypothetical election, we provided some of them (selected at random) with information about a highly publicized corruption scandal involving 23 of the politicians included on the party lists, from both the incumbent and the main opposition party. One might expect that in the open list system, voters would be less likely to choose candidates who had been involved in this corruption scandal when they had been reminded of their involvement. But we did not find any statistically meaningful difference in the vote choices of those who received this additional information, as compared to other respondents who did not. This casts doubt on the idea that lack of information is the main obstacle preventing voters from voting against corrupt politicians.

Taken together, our results challenge the optimistic view that providing voters with information and giving them more formal control through more “open” electoral systems are helpful tools when fighting corruption.

This blog was originally published on GAB | The Global Anticorruption Blog Law, Social Science, and Policy and was republished with permission.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author’s views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.

You might also like:

From Tbilisi to Washington: Is there too much focus on elections?

Can democracy function if societies don’t understand politics? 🔊