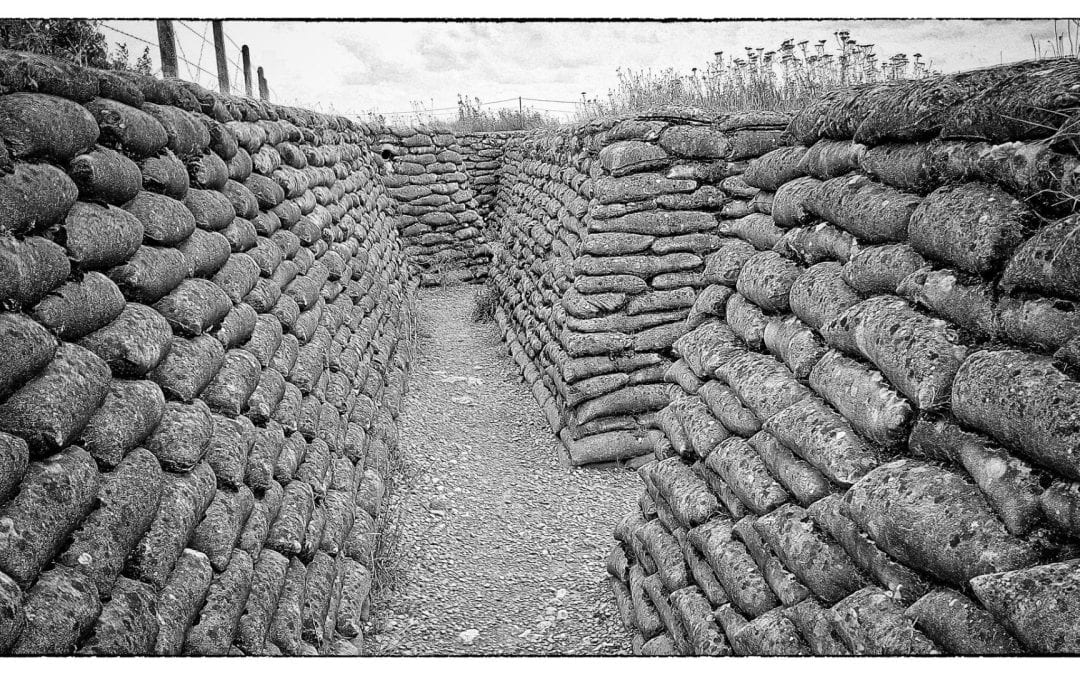

Craftnighter / Wikimedia Commons

Jeffrey McNeill, Massey University

It was observed […] that the English had slain wounded and captured German prisoners.

So reads a disturbing war diary entry of the Bavarian 18th Regiment from June 7 1917, quoting one Schütze (Rifleman) Jakob Eickert of the 2. Machine Gun Company.

Another Bavarian soldier, Karl Kennel, was nearly one of those slain. He later wrote to the Red Cross that he and his friend Friedrich Christoffel were wounded when enemy troops bombed their dugout.

They emerged, belts unbuckled in surrender, and begged for mercy. Christoffel was on his knees with hands raised when a soldier pointed a gun at him and pulled the trigger. Kennel escaped death by rolling into a shell hole.

The Bavarians were fighting the New Zealand Division that day in 1917, at the very bloody Battle of Messines. Both Eickert and Kennel were describing New Zealand soldiers’ actions – then, as now, war crimes.

These days, New Zealanders and Australians tend to place their soldiers on pedestals on Anzac Day. We are led to believe these mostly volunteer civilian soldiers were an exceptional body of fighting men (something the men themselves also believed). But this reputation came at a price.

Alexander Turnbull Library

‘It was quite common’

Anzac soldiers should have known such killing of enemy prisoners was forbidden. The British Manual of Military Law, which codified the 1907 Hague Convention on land warfare, forbade soldiers from killing or wounding an enemy who had surrendered at their own discretion. “This prohibition is clear and distinct”.

Furthermore, officers and men alike were expected to know these regulations. Yet as I show in my book, Taking the Ridge: Anzacs and Germans at the Battle of Messines 1917, New Zealand soldiers’ diaries and memoirs confirm that killing prisoners and the wounded was a feature of the fighting at Messines, and likely elsewhere.

Some diary entries were matter of fact: “Our fellows used the steel [bayonet] a great deal so there were not so many prisoners as there might have been,” wrote one soldier. “Lots of Germans were bayoneted on the ground, wounded men. It was quite common,” wrote another.

One wrote of speaking to a German he took prisoner: “He was like the rest, full of the tales of British cruelty to prisoners. They all expect to be killed and I am afraid I saw some very dirty work done, which might account for the tales they hear.”

Others simply distanced themselves from such actions: “I’m proud to say it never entered my head to [kill wounded men] or shoot down people with their hands up,” wrote one.

There are also examples of compassion and soldiers comforting wounded Germans. But other actions were contingent on the circumstances – a case of “them or us”. When Rifleman Edward Miller and his officer struck a dugout of “Fritzes”, for example, they took prisoner a solitary German. But they took no chances with another group of Germans, one holding up a white handkerchief – they were “finished off”.

Jeffrey McNeill, Author provided

‘Officially sanctioned’

The New Zealanders sent some 300 prisoners to the rear in the battle. But that is only half the number the adjacent British 25th Division took prisoner. The discrepancy suggests particularly savage fighting by the New Zealanders.

Individuals must bear responsibility for their actions, but so must their commanders. The New Zealanders’ senior officers’ support for killing prisoners tended to be tacit. A bloodcurdling lecture on bayonet use by the Scottish firebrand Major Ronald Campbell to the New Zealanders before the Somme attack in 1916 gives some insight.

Campbell had discouraged taking prisoners. Rather, soldiers should bayonet surrendering enemy soldiers when they put they hands up – “that’s your chance to stick him in the soft part of the belly where the bayonet goes in easily and comes out quickly”, Campbell instructed.

The New Zealand Division’s commander, General Andrew Russell, approved: “Lecture by Major Campbell on bayonet fighting – very good indeed.” Captain Lindsay Inglis, a law clerk before the war and a brigadier in the next war, did not. He wrote in his diary:

It would be interesting to know to what extent [these lectures were] responsible for deeds of the kind which even in war amount to nothing less than brutal murder […] We were astonished that it should have been officially sanctioned.

Lest we forget

Airing this dirty laundry may seem inappropriate for Anzac Day, especially as many men did not commit war crimes. But knowing what happened in battle provides a more complete understanding of their experience.

War is brutal. Despite headlines at the time proclaiming Messines a great New Zealand victory “for extraordinarily light losses”, some 3,700 New Zealanders were killed or wounded in the battle. Around 3,600 of the Bavarians opposite them were killed, wounded or taken prisoner. Only three officers and 30 men of the three Bavarian front-line battalions returned.

And war is still brutal today, with similar consequences. Investigations into the behaviour of Australian and New Zealand troops in Afghanistan in recent decades only underline the contemporary relevance of older misdeeds.

This includes the inquiry into the conduct of New Zealand SAS troops during Operation Burnham, and the Australian Brereton Report, which found serious breaches of ethical, legal, professional and moral responsibilities by Australian Defence Force soldiers.

By acknowledging this kind of behaviour has occurred during past wars, the public will perhaps be less reluctant to accept evidence that it can still happen. It should also mean the military itself will work to ensure it doesn’t happen again in the future.![]()

Jeffrey McNeill, Senior Lecturer in Resource & Environmental Planning, Massey University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.