By Paul Panckhurst

There’s evidence that looking at paintings can reduce stress and anxiety. A researcher wants to know if this phenomenon can help surgery patients heal.

Pablo Picasso once said, “Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life.”

The artist was talking about the stillness and focus gifted by a good painting.

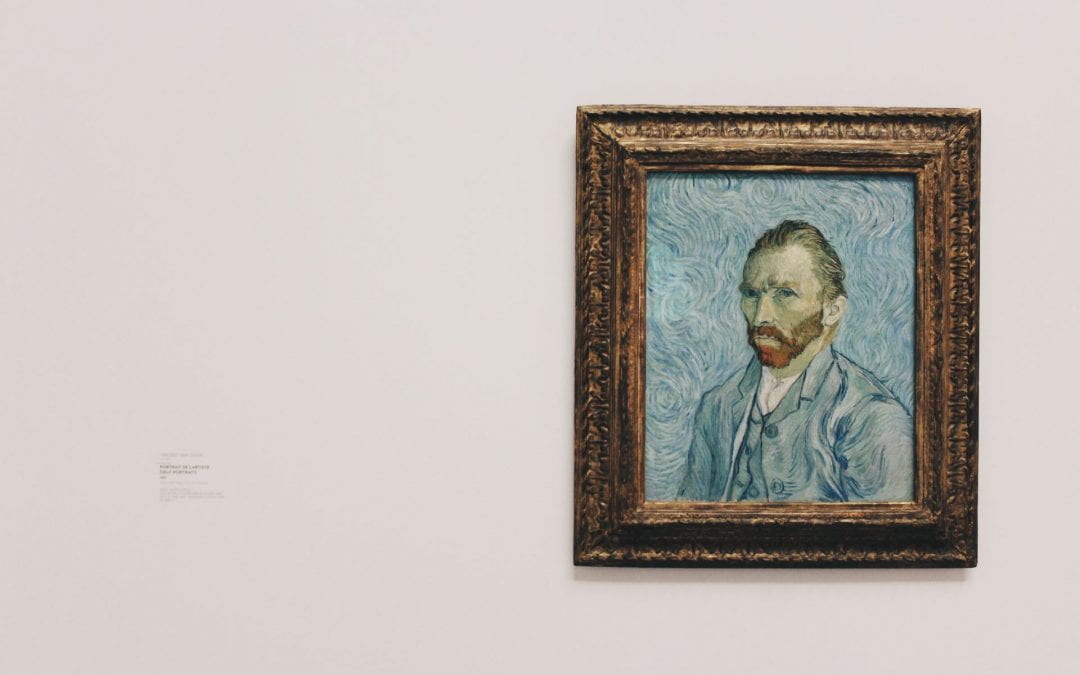

Paintings, good, bad and indifferent, hang on the walls of hospices, hospitals, universities and corporate offices. Their presence explained by any number of reasons, but Picasso’s words resonate.

Art and, in particular, paintings, take us somewhere else. However, researchers want more than rhetoric and anecdote, they need evidence. Scientists have wondered about the beneficial aspects of viewing artwork for decades and they have devised a range of experiments.

In the Netherlands researchers showed a balance of digital projections of ‘beautiful’ and ‘ugly’ paintings to a group of laboratory workers and a group of fine arts students. In Australia people living with dementia were taken to see artworks in a gallery and measurements were taken of their cortisol, a stress hormone.

In the United States patients aged between 5 and 17 in a paediatric hospital were shown large nature artworks and another group were shown abstract works. The heart rate, blood pressure and respiratory rate of the two groups was measured. In Switzerland 75 members of the general public aged between 18 and 35 were shown artworks of Flemish expressionism. Their heart rate, variability of the heart rate and skin conductance was noted.

All but one of the studies that measured self-reported stress found a significant decrease after viewing artwork. There was physiological evidence in four studies showing lowered blood pressure and decreased heart rate in two studies. One study found that fine arts students experienced a lift in their heart rate when viewing ‘beautiful’ paintings while other participants experienced a decrease.

One study found that it did not matter if the artworks were physical or digital reproductions. It did matter that the artworks needed to depict nature. Abstract and expressionist artwork had the reverse impact.

These are some of the findings from a recently published paper. Lead author Dr Mikaela Law, a researcher in psychology at the Faculty of Medical and Health Services says, “We decided to conduct a scoping review, as there has been no research which had systematically combined the evidence for the effects of viewing artwork on stress outcomes.”

Combing through databases, she found 3882 potentially relevant publications, that were filtered down to 14 research articles where researchers had actively tried to measure changes in stress or anxiety levels from viewing paintings.

The big takeaway? “Looking at art is good for you. That’s the finding we expected. The finding that nature artwork seems to be the most beneficial is important, as this provides a guide as to what types of artworks could be placed in stressful settings, including medical areas and workplaces.” Law says.

The paper proposes two theories for the benefit of viewing scenes of nature, landscapes, forested mountain ranges and seascapes. The evolutionary theory proposes that because humans evolved in a natural environment, we find it easier to process nature than artificial environment and in doing so find ourselves restored. The other idea, known as attention restoration theory, says the presence of nature counteracts mental fatigue caused by stress, reducing cognitive strain.

Law says, “The theories work well in conjunction with each other. We are evolutionarily predisposed to experience relaxation and restoration in natural environments, which is why nature artworks could be particularly beneficial.”

For Law the next step is to look for any benefit beyond stress-reduction. Can the mere act of viewing artworks improve healing from wounds? Would an artwork session before surgery reduce patient anxiety and improve surgical outcomes? The mind is powerful. If provided with calming scenes from nature, patients might experience less post-operative pain and a speedier recovery.

This article was originally published as part of The Challenge series and was republished with permission.

The Challenge is a continuing series from the University of Auckland about how researchers are helping to tackle some of the world’s biggest challenges.

Mikaela Law is a Researcher in Psychology at the University of Auckland.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author’s views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.

You might also like: