By Ian Scoones & Andrew Stirling

Governments haven’t found the magic formula for predicting the way people and diseases will interact with each other.

Are you getting used to uncertainty? The feeling that things are uncertain – in financial markets, cities, the climate, new technologies, the spread of a pandemic – seems to be getting ever more intense. Familiar structures that prop up modern life, even those that looked serious and powerful, seem more and more flimsy. Messy assumptions hide behind hard facts, and even sophisticated models can’t seem to keep up with unfolding reality. The gaps in our knowledge about the world are combining with the unpredictable ways that things actually happen.

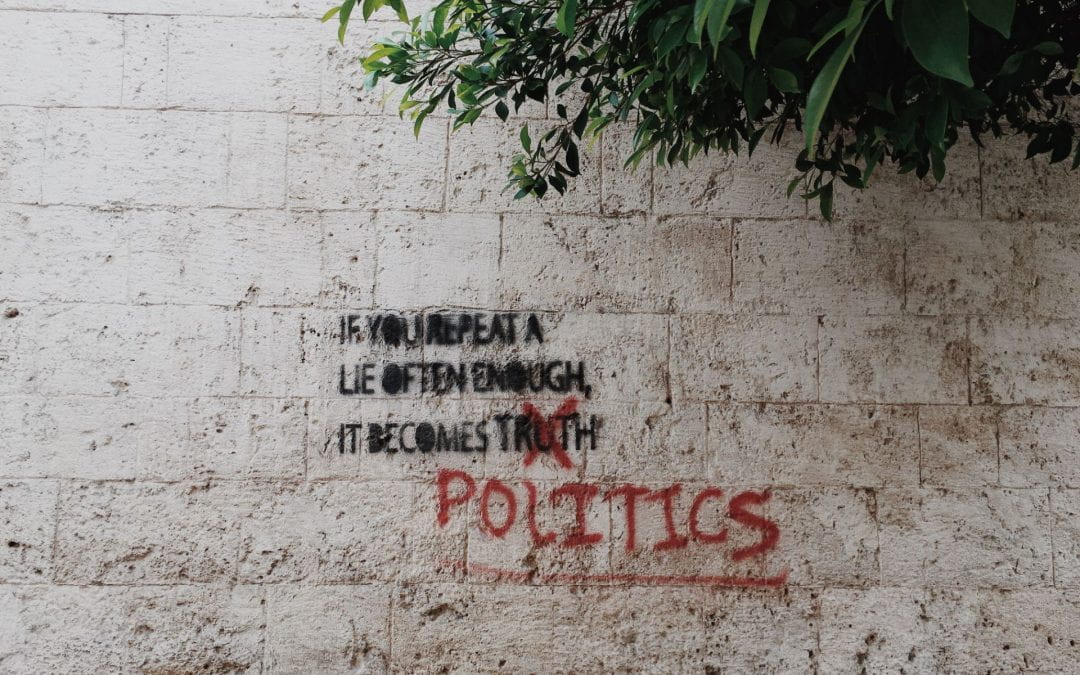

All this adds up to a wild variety of different experiences of uncertainty, which then get reflected in how people plan and respond to the world around them. And yet politicians and leaders repeatedly talk about “minimising risks” and “taking (back) control”. In the intense race towards goals or away from emergencies, uncertainties get left by the wayside.

As we explore in a new open access book, The Politics of Uncertainty: Challenges of Transformation, people are right to feel uncertain. But uncertainty is more than a vague feeling of not knowing what’s going on, or being caught off-guard by the unexpected. From measurable risks to the possibility of surprise, there are different flavours of uncertainty, and maybe even more different ways to adapt and respond.

Nearly a century ago, the economist Frank Knight made the distinction between risks and uncertainties: “A measurable uncertainty, or ‘risk’ proper … is so far different from an unmeasurable one that it is not in effect an uncertainty at all.” In other words, there are some cases where you can put a number on the likelihoods of different outcomes – and some where you just can’t.

There are other flavours too. One is ‘ambiguity’, where people disagree about the possible outcomes of a decision. This disagreement might be about people’s ideas of benefits and harms or what alternatives should be on the table. A fourth flavour is ignorance – where there are things ‘we don’t know we don’t know’, leading to the possibility of surprise.

These other flavours of uncertainty are inconvenient truths. There’s a constant pressure to put the unknown into numbers. This might come from researchers themselves, wanting to get their message across in simple terms. Or it might be driven by decision-makers demanding clarity. Whatever the reason, overly focusing on risk leaves out the more messy parts of reality – in other words, most of it.

This matters because those messy flavours of uncertainty are so important to so many areas of life. They are part of people’s everyday experience all around the world – from farmers seeking insurance against droughts, to people in managing power grids or water supplies, fishers and farmers in coastal India or Bangladesh coping with climate change, villagers responding to infectious diseases, migrants on the search for a better life, a community building a place of sanctuary or refuge.

They’re written in the bodies of those undergoing chronic stresses and anxieties, baked into everyday rituals and habits, often below the surface, not easily seen or documented. Professional managers of power networks or transport systems – where it’s really important things don’t explode or grind to a halt – have to ‘manage’ the non-measurable uncertainties without seeking to control everything. Far away from the control rooms and power stations, shepherds on high mountains or dusty plains do something similar – as they plan beyond their control for changes in the weather, the fluctuations of markets, the health of their flocks.

Space for alternatives

In all these circumstances, uncertainty can be exhausting and stressful – making it hard to plan ahead and make decisions – but it can also open up new possibilities. If the future isn’t written in advance, maybe space can be made for alternatives.

These kinds of uncertainties may be messy, but we don’t just have to wave our hands or back away from them. There’s no shortage of approaches that can help policy makers or organisations respond to them – from adaptive management, to experimentalist approaches, to deliberative governance. For example, in rapidly-expanding cities, ‘smart’ systems promise to help track flows of people and manage transport, energy or water. For some, they may even provide a way to monitor ever more details of daily life, threatening privacy. But in some places, such as Milton Keynes in the UK, the technology is being used in more tentative, experimental ways as planners learn as they go. Key to these experiments are conversations with local people that allow them to shape the way the technology is used – in keeping with the city’s history of innovation. Rather than rushing into building a ‘smart city’, different technologies are being tried, tested and discussed.

In all of these approaches, it’s important to be able to learn bit by bit and reflect as you go along, and leave space for negotiation, maybe even pursuing several different possible outcomes at the same time. They also require people to engage with different sources of knowledge and experience – benefiting from diversity, rather than relying on one narrow model of expert advice. Solidarity and collective action, mutual aid and equality are vital ingredients. Humility and care are not luxuries, but practical necessities.

Humility and care are not luxuries, but practica necessities

Given this rich diversity of uncertainties, and the many approaches that already exist to respond to it, it’s shocking how much effort is made in trying to squeeze uncertainties into a ‘risk’ box.

But on reflection, perhaps it’s not so surprising. After all, modern life is defined by a powerful story of linear progress: a hard-wired ‘one-track race’ to the future, guided by science and economic growth. The solutions – ‘climate-smart agriculture’, ‘clean development’, ‘geo-engineering’, ‘green growth’ or ‘zero-carbon economies’ – rely on futures being predictable, and risks being controlled and minimised. Why would such a vision admit an uncertain future?

In the end, if the future is already written and determined, mapped out across a narrow set of possibilities, there’s little hope for imagining alternatives. Powerful actors and a well-oiled machinery of progress would dominate the next chapters in the story. But these uncertain times suggest that perhaps those big shaping forces are open to question.

Learning from below

Learning from uncertainties ‘from below’ – through the stories of vulnerable, marginalised people living in precarious circumstances – can be a powerful challenge to confident predictions of control. And recent experiences of a world caught off-guard by a global pandemic suggest that governments haven’t found the magic formula for responding to surprise, or predicting the way people and diseases will interact with each other.

Maybe we all need to become a bit better at recognising uncertainties, especially where they’re hidden or obscured by states of emergency or a race to a brighter, pre-written future. Embracing, discussing and preparing for uncertainty, in all its variety, will be a vital part of emancipatory change for many years to come.

This article was originally published on openDemocracy.net and has been republished under a Creative Commons Licence. If you enjoyed this article, visit openDemocracy.net for more.

Ian Scoones is a professorial fellow at the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex.

Andrew Stirling is a Professor of Science & Technology Policy at the University of Sussex.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author(s) views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.

You might also like:

Will COVID-19 transform world politics?

What will a post-COVID-19 world look like?