By Nancy November

The 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth would surely be loud, public, monumental, teleological, triumphant, heroic—like the music of the man himself. Right? Wrong, on both counts.

Along with other Beethoven scholars, students, performers and fans, I expected 2020 to be big: The 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth would surely be loud, public, monumental, teleological, triumphant, heroic—like the music of the man himself. Right? Wrong, on both counts.

Of course, it started off that way. I attended ‘Beethoven Perspectives’, an epic five-day, two-stream international congress, which took place at Beethoven-Haus, Bonn from 10-14 February 2020. Each day featured one of five main symposia on the following provocative themes: the political Beethoven; a global Beethoven; the Bonn Beethoven; the creative Beethoven; and Beethoven as recipient of others’ music. These symposia were each organised by pairs of scholars, one from Bonn, the other from elsewhere, who delivered thought-provoking introductions to the respective topics and panels of speakers each morning. It was a monumental affair, with associated concerts and art exhibitions. I left the conference, and Europe, with Beethoven ringing in my ears, especially the monumental late works—the Ninth Symphony, the Missa Solemnis, the late string quartets.

And then silence or rather the constant ping of emails announcing cancelled concerts, conferences, and public life. One musical experience from late March stands out: in the stillness brought about by the almost complete absence of traffic and pedestrians, the birdsong became much more audible than ever before. So Beethoven Year was going to be celebrated in a different way—and one that is, as it turns out, equally appropriate. After all, the heroic, monumental public aspects of Beethoven’s life and music represent just one side of a complex. Equally prevalent were the private, intimate, songful, melancholic, and pastoral impulses, which coexisted side-by-side throughout his career.

Consider the Fifth and Sixth symphonies, which are very different in tone and style: one abstract and dramatic, the other programmatic and relaxed. And, as we sit within our private family bubbles, perhaps still hearing the birdsong and feeling perhaps just a touch of nostalgia for the ways things were, and melancholy about the way things are, let’s join Beethoven in Napoleonic Vienna and escape into the pastoral world.

As so often with Beethoven’s music, the subsequent history and reputation have to a large extent obscured the impulses that first produced the work. The Pastoral Symphony has been part of the standard repertoire from 22 December 1808, to the present day. But its reception has been chequered, and it has not always been well understood—especially as regards its programmatic nature—that is, its ‘Pastoral’ character. In what follows I would like to provide you with a little context for this symphony, so that you can appreciate some of the resonances—intellectual, social, and musical—that the listener of Beethoven’s day might have experienced.

First it’s important to understand that concert life in Vienna just getting going—it was difficult for a single composer to present work to the public on a regular basis. In the first decade of the nineteenth century, the violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh was the main figure to attempt to hold regular subscription concerts. His were chamber music concerts. The concert on 22 December at which the Sixth Symphony was premiered was a one-off. Like other musicians, Beethoven was forced to organise his own concerts, arranging the hire of venue, securing musicians, printing tickets, and placing advertisements. Beethoven’s aristocratic patrons mainly supported him as a teacher, pianist, and composer of piano and chamber music—not as symphonist. Writing in a Viennese newsletter of 1808, a correspondent noted the retreat into private music-making, brought on by political unrest, invasion, and the closing down of public concert life in general:

In this capital, few houses will be found in which this or that family does not entertain itself with a quartet or with a piano sonata and, thanks be to Apollo, the once so despotically widespread card playing has fallen out of fashion… Yet so much is devoted to the so-called chamber music that there is little opportunity for full orchestral works, for symphonies, concertos etc.

And the opportunities were to worsen: the concert of 1808 marked the end of a period of intense public exposure for Beethoven’s symphonies. In 1809-10, reflecting the general decline in cultural activities due to the threat of invasion and subsequent occupation by the French, the number of symphonies performed in Vienna fell markedly.

In fact, several notable works of the ‘heroic decade’ (1800-1810) show a marked retreat into the pastoral tradition, invoking pastoral images that can be traced back to the Renaissance. Works like the ‘Pastoral’ Symphony and the Piano Sonata in D major, Op. 28 (1801) draw on stylistic features that form part of the music pastoral tradition include: drones, dancing rhythms and meters, piping melodies, and repetition. Modern listeners looking for traces of the Pastoral tradition in music before Beethoven’s Sixth can think of works like Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, Handel’s Messiah, or Bach’s Christmas Oratorio.

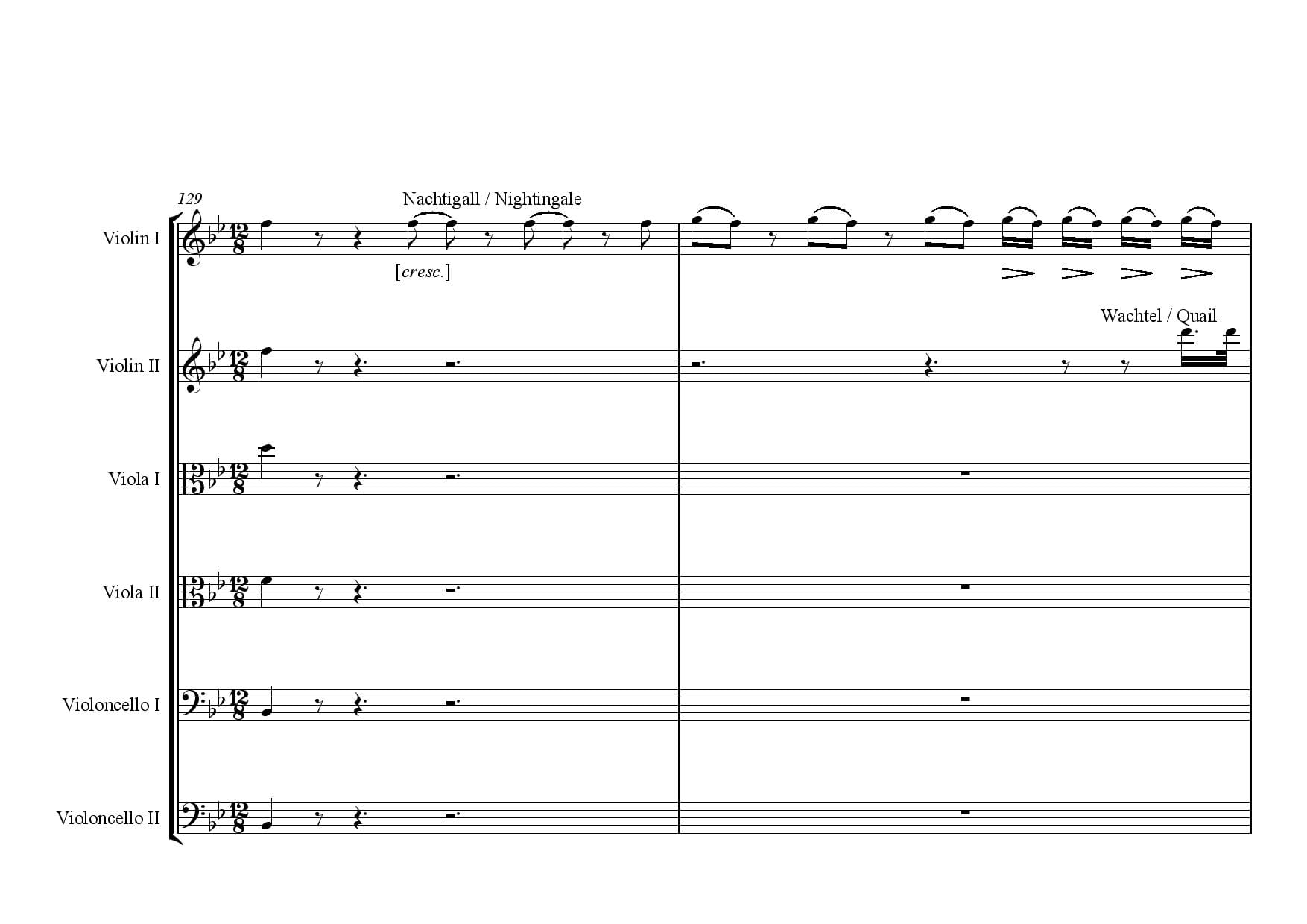

A distinctively Austrian form of the long tradition of representing bird songs in music was the custom of including parts for especially constructed instruments. Example 1 shows the birdsong passage in an arrangement of the second movement (‘Szene am Bach’) for string sextet by Michael Gottfried Fischer (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1810). Arrangements of the work (and indeed all of Beethoven’s symphonies) became popular in the nineteenth century, a way of re-hearing concert music in a time when chamber music in the home flourished, before symphony orchestras became widespread and before the age of the gramophone.

On a more personal level, Beethoven himself greatly enjoyed the natural world and sought rest and inspiration there. In letters he expresses this enjoyment of things pastoral. For example, in a letter to Marie Bigot of 4 March 1807 he writes: ‘The weather is so divinely beautiful—and who knows whether it will be like this tomorrow?—so I propose to fetch you about noon today and take you for a drive…’. And in a letter of 26 July 1809 to his publisher Breitkopf und Härtel he notes: ‘The whole course of events [meaning the French occupation of Vienna] has in my case affected both body and soul. I cannot yet give myself up to the enjoyment of country life which is so indispensable to me’. Then in a letter of May 1810 to Therese Malfatti he states: ‘How fortunate you are to be able to go into the country so soon. I cannot enjoy this happiness until the 8th, but look forward to it with childish excitement. How delighted I shall be to ramble for a while through the bushes, woods, under trees, through grasses and around rocks. No one can love the country as much as I do. For surely woods, trees and rocks produce the echo which man desires to hear’.

Not surprisingly, then, the Pastoral impetus is found in numerous Beethoven works: the ballet The Creatures of Prometheus, the Septet, Op. 28 and Op. 101 Piano Sonatas, the Missa Solemnis, and in his songs, to name a few examples. Despite some contemporaries complaints about overt pictorialism in music, Beethoven nonetheless included a certain clear-cut pictorial passaged in the Sixth Symphony. In his score annotations we find draft titles for the individual movements, and labels for certain pictorial features, almost as if he took delight in this. The labels for the pictorial effects were clearly intended for the musicians, rather than the audience, however, while the movement titles were certainly to be shared with the audience. Beethoven labeled the three bird calls at the end of the third movement (but without identifying specific birds) and showed what amounts to a childish glee in identifying elements of the storm movement, labeling ‘Donner’ (thunder), ‘Blitz’ (lightning) and ‘Regen’ (rain), against the respective musical figures. The movement titles read:

Awakening of happy feelings on arrival in the countryside

Scene by the brook.

Happy gathering

Thunderstorm

And finally Shepherd’s song. Grateful thanks to the Almighty after the storm.

Even though Beethoven took some care to align his work with ‘the expression of feelings’, rather than with simple object painting, early listeners wanted to understand the work as concretely pictorial. From as early as 1829, for instance, performers mounted stage productions of the ‘Pastoral’ in which Beethoven’s program was acted out amidst appropriate scenery. The notorious Beethoven biographer Anton Schindler contributed to this idea in 1860, claiming, supposedly on Beethoven’s authority, that he had been able to identify a previously unknown bird, the ‘Goldammer’ in bar 58 of the second movement! This is an arpeggio figure, which is heard several times, amongst other bird calls. Sir George Grove concluded that Beethoven was pulling Schindler’s leg, noting that ‘Goldammers’ did not sign arpeggios! But other writers on the Pastoral Symphony took Schindler’s comments on board, and reinforced the impression that ‘word painting’ was central to the symphony’s meaning.

What’s easily missed, in this view of the work, is a broader understanding of how this work partook of the pastoral tradition around 1800. Important to this larger conception is a sense of how Beethoven treats time, on the large scale, in this symphony. The first two movements unfold deliberately, rather than driving towards their conclusions. Harmonies emerge slowly, themes evolve over lengthy expanses, and there is little of the end-orientation found in his contemporaneous instrumental works (the Fifth symphony is a prime example). On the other hand, the following two movements move at a frenetic pace, and run on from one to the next with scarcely a pause. The sense of dynamism that characterizes the ‘storm’ movement is readily appreciable. Time slows again in the finale, so that the sense of leisurely unfolding that characterises the first two movements returns.

Beethoven’s Pastoral Time probably resonates with more than a few of his 2020 scholars, students, performers and fans. Barred from the concert hall, lecture hall, or any other kind of hall, we retreat into the cyclic rhythm of lockdown family life. In lockdown time zone we are forced to slow down, and the usual markers of time—which prevent Thursday from becoming Blursday—the are removed, replaced by a sameness, and that odd kind of quasi-silence, punctuated by birdsong on the one hand, and the ping of email on the other. In this pastoral moment, as Beethoven turns 250, let’s try to populate a different world map of growing case numbers: https://pastoralproject.org/meet-our-participants/

Nancy November is an Associate Professor in Musicology at the University of Auckland and a member of the Europe Institute. She is the author of several books on Beethoven as well as an expert in late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century chamber music.

For more on the pastoral project click here.

For more on the Europe Institute click here.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author’s views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.