By Chris Benton

What does the discovery of a new dwarf planet tell us about the outer parts of our Solar System?

Astronomers have recently announced the discovery of a new dwarf planet in the extreme outer parts of The Solar System, which supports evidence for the highly-speculated and much larger “Planet-X”. This new finding has important implications for future planetary science and observational research, but is also part of a bigger picture of how our understanding of the solar system has progressed.

The discovery of the distant planet Pluto beyond the orbit of Neptune in 1930 by Clyde Tombaugh was the first clue of there being more to the Solar System than eight planets, an asteroid belt, and some nomadic comets. In the 1950s Dutch-American astronomer Gerald Kuiper hypothesised the existence of a collection of small bodies in the region of Pluto which was the source of short-period comets, with orbital periods less than 200 years. At the same time, Dutch astronomer Jan Oort hypothesised there to be a much larger sphere of icy bodies up to a light year, equal to 10 million million kilometres, away from the Sun giving rise to long-period comets, with orbital periods greater than 200 years.

Over recent decades, with powerful telescopes, computers, and sensitive CCD imaging, increasing numbers of small bodies in the outer solar system have confirmed Kuiper’s hypothesis, now known as the Kuiper Belt. Astronomers continue to discover more objects in this distant neighbourhood, each one helping to build a picture of what might be out there. These include dwarf planets, which are by definition large enough for gravity to have shaped them round, and have highly elongated orbits taking them well beyond the Kuiper Belt into what is known as the Inner Oort Cloud.

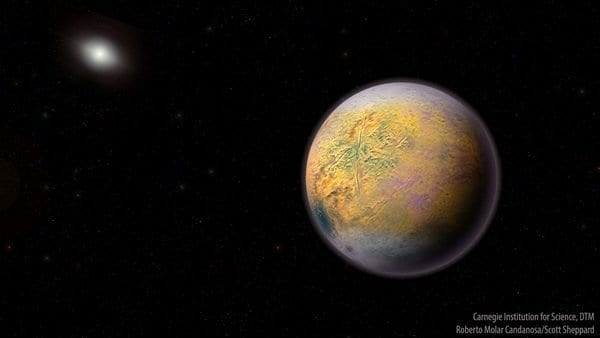

Recently a group of astronomers led by Scott Sheppard from the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington announced that as part of a sky survey, they had discovered a new dwarf planet known as 2015 TG387, which has acquired the nickname “The Goblin”. While only small with a diameter of 300 km, The Goblin may provide a clue to the existence of a much larger elusive planet, known simply as Planet-X, speculated by astronomers in 2016 to exist in the far-reached location of the Inner Oort Cloud.

The key to this clue lies in the study of The Goblin’s orbit over the past three years, and using computers to calculate its full orbital properties around the Sun. In comparison to the Earth’s distance to the Sun (which is approximately 150 million kilometres, known as one Astronomical Unit) The Goblin is currently 80 Astronomical Units from the Sun, or 2.5 times farther out than Pluto. It has an extremely elliptical-shaped orbit with its closest approach to the Sun (perihelion) at 65 AU and the longest distance from the Sun (aphelion) 2,300 AU. Calculations indicate it will take 40,000 years to complete each orbit of the Sun.

Further analysis of these orbital properties shows the point of the perihelion of this object is similar to the other two known Inner Oort Cloud bodies (IOCs), Sedna and 2012 VP113 (as shown in Figure 1). Furthermore, the orientation of The Goblin’s orbit is similar to that of a cluster of outer Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs).

The relevance of these shared orbital properties is that computer simulations of this new data supports the hypothesis of the existence of a much larger distance planet that is gravitationally influencing and guiding the planets into such stable orbits (Sheppard et al. 2018). Moreover, the discovery of The Goblin and determination of its orbit allows astronomers to estimate the density of objects further outwards in the Solar System, with the conclusion they expect there to be about two million IOCs greater than 40 km in diameter (ibid).

This recent announcement by Scott Sheppard and his team highlights the ongoing progress in learning more about this relatively unexplored part of the Solar System, as well as how computers and the mathematics of orbital dynamics are helping to reshape our current ideas. Further sky surveys and planetary search programmes will follow in this exciting and rapidly growing field of planetary science.

References:

Sheppard, S.S., Trujillo, C.A., Tholen, D.J. & Kaib, N. 2018, arXiv: 1810.00013

Chris Benton is a semi-retired General Practitioner studying for a Masters in Astronomy at Swinburne University in Melbourne. He is also a member of the Auckland Astronomical Society.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author’s views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.