By Annie Goldson

Award-winning documentary maker, Annie Goldson, discusses how the subject of her latest film — the larger-than-life tech entrepreneur Kim Dotcom — challenged her to consider the role of authenticity and performance in documentary.

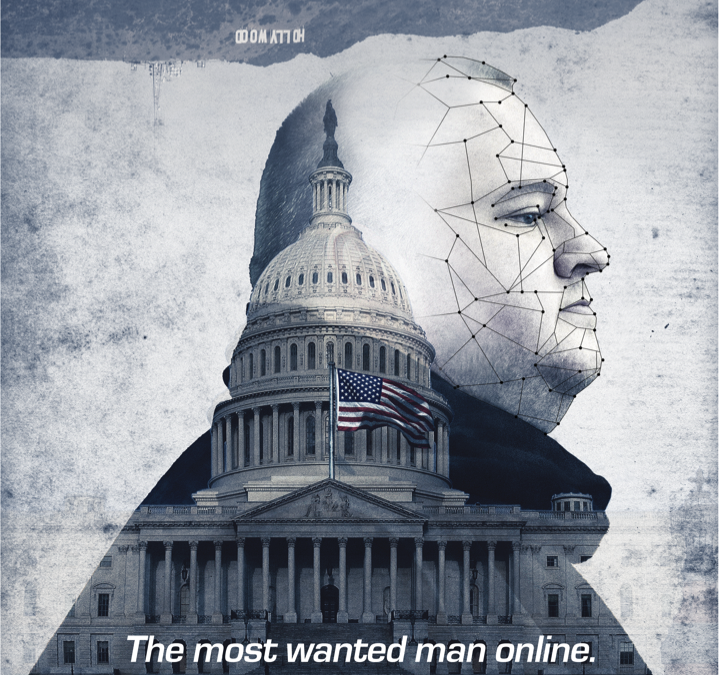

Many readers will be familiar with the controversial central character of my new film, Kim Dotcom: Caught in the Web. For those who are not, this trailer will help:

The documentary follows the life and times of the tech entrepreneur and founder of file-sharing site Megaupload who, along with his colleagues, was arrested and indicted for allegedly running a business dedicated to copyright infringement (aka Internet ‘piracy’). The men were arrested after a high profile 2012 raid by New Zealand police on Dotcom’s Auckland – an action coordinated by the FBI and based on their intelligence. The film charts Dotcom’s fight against extradition to the US where he faces a slew of charges. If found guilty he could spend up to 80 years in prison.

The film is partly a biography and partly an attempt to look at the issues behind the Dotcom case, which are bigger than the man himself.

There are three major issues that occupy the film. The first is file-sharing, infringement, piracy – call it what you will, and questions of how we consume entertainment and information in the digital age. How do we harness the power of the Internet to ensure that the creative sector gets genuine reward and sustenance?

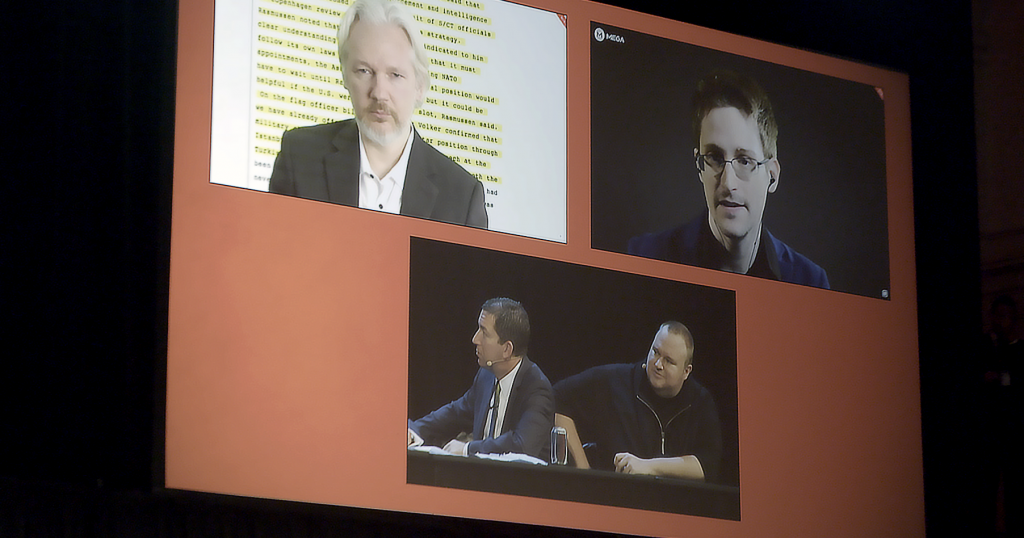

Still from the film. Kim Dotcom, Glenn Greenwald, Edward Snowden and Julian Assange at the “Moment of Truth” event held in New Zealand.

A second issue explored in the film is privacy and surveillance. Dotcom was spied on illegally by New Zealand’s Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB), part of the international Five Eyes intelligence network. How does knowing we are under constant and mass surveillance impact on our personal relationships, our business dealings and, critically, our communication and political discussions?

Finally, domestic sovereignty: what does the joint and, many believe, over-the-top policing effort carried out by NZ forces and the FBI mean for NZ’s own democratic processes? Did an alleged case of copyright infringement against US entertainment corporations justify the use of paramilitary efforts half a world away?

But aside from these explicit themes of the documentary, Kim Dotcom also caused me to reflect on authenticity and its role in documentary. Authenticity plays a special role in documentary. We know, fundamentally, that drama is not authentic: the commonplace phrase being “suspension of disbelief”. We all know that we are watching a performance. This is not to say that drama does not generate authentic feelings and emotions. But we all know drama is performance, no matter how much we feel immersed in the story world.

By contrast, authenticity is fundamental to the mission of documentary. Audiences know there is a filmmaker behind the image and sounds, but they are meant to believe that what they see bears witness to the way the world is. And filmmakers are often drawn to documentary when we want to engage audiences in questions or issues that pertain to the historical world we all share.

Nonetheless, documentary involves performance too. Documentary theorist Bill Nichols has called interview subjects in documentaries “social actors”, suggesting that they “play themselves” on camera, even where they continue to conduct their lives more or less as they would have done without the presence of the camera there.

Psychologists and philosophers have often questioned the idea of an authentic, essential self, suggesting that we play ourselves all the time. And that performance of self is often heightened when we are in front of a camera. Nonetheless, most of us, both in everyday life or in front of a camera, will try to be “true to ourselves”.

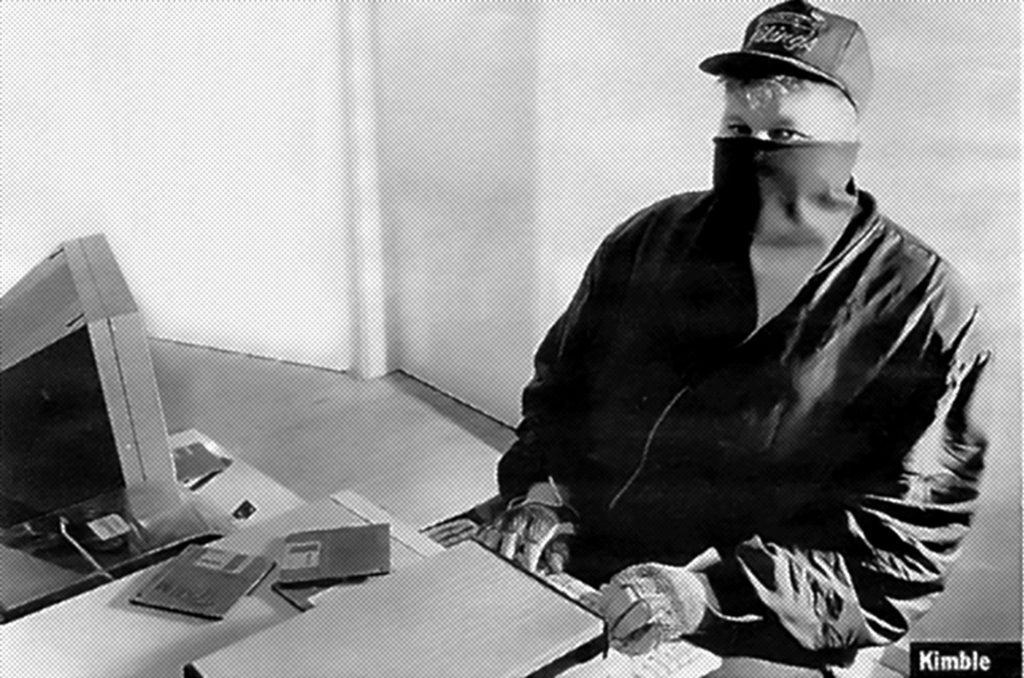

Not so for my Great Pretender, Kim Dotcom. He has had a life-long preoccupation with his own image, not only controlling it but also publicising it. His first well-known persona, Dr. Kimble (taking his name, ironically enough, from TV series The Fugitive) drew on the ethos of the hacker, where using pseudonyms and aliases were commonplace. Dr. Kimble used his “hacker cred”, partly derived from minor criminal charges, to create the computer security company Dataprotect. Kimble became the poacher turned gamekeeper, where former hackers protect companies from hackers like themselves. His character then evolved again into Kimvestor, the young risk-taking tech investor, and his alter-ego Kim Jim Tim Vestor. Finally he arrived at Kim Dotcom, with his side specialty, Hollywood’s Dr. Evil.

Often hackers use anonymity to lurk in the internet shadows, but not Kim. This kind of performance of self both pre-dated and anticipated the social media world of today. Several years before Facebook launched in 2004, Kim’s Kimvestor was fashioning an online identity and engaging in digital impression management. His website was dotted with images of his partying lifestyle, including selfies of him posing with famous (apparent) friends, as shown in this clip:

Dotcom saw that to be a successful investor, you had to be seen as financially successful. No one backs a loser in Kimvestor’s world.

Kim Dotcom’s last persona, Dr. Evil, was so effective that many in the media industries read it as the “truth”. There he was, living in that huge house with all of those cars, the girls, hot-tubs, luxury yachts, and outrageous number plates, rubbing so much salt into the wound: they believed he truly was the devil incarnate. He was doing this with what they believed was their money. Oddly though, his extravagant lifestyle parodied the representations peddled by those very companies, which rely on the glamour of the A-lister Hollywood star.

While I found Kim Dotcom’s identity performances very interesting, I also recognised that his preoccupation with his own image would be both a challenge and a potential bonus to documentary filmmaking. On the positive side, Dotcom’s outlandishness meant that there would be great archive material. He was a tireless self-documenter, resulting in a rich archive of colourful images that we were eventually able to negotiate access to.

But on the negative side, there was always to be a problem working with a character so able to control and manipulate his image: would I be able to “get under his skin” sufficiently to satisfy the documentary need for authenticity? After all, the onus is often on the filmmaker to reveal the “real person”. Filmmakers and audiences alike hanker for those moments where the subject is off-guard, emotional, and hence authentic.

While this issue is especially relevant when dealing with an extreme character such as Kim Dotcom, it also raises a more general issue about the relationship between documentary filmmakers and their subjects. There is a longstanding critique accusing documentary filmmakers exploiting their subjects, in ethnographic but also political documentary. Filmmakers are seen to have too much power, at times throwing their subjects under the bus either to serve their political agenda or to increase their fame and critical or commercial success.

But I would argue that the documentary subjects may also exert control over filmmakers, and sometimes the ultimate control. They can walk away, undoing years of work. Maintaining access is a delicate dance of power between filmmaker and subject, especially when they come from very different worlds. This was the case for me, working with Dotcom, who is a complex, controversial character who dances in the ethical and economic grey zones of the entrepreneur. How much control a documentary’s subject exerts and how much a filmmaker is willing to compromise to keep them on board is hard to determine.

Traveling to several countries and around NZ with this film, I have been asked similar sets of questions that prod at this issue: Was Kim Dotcom always on board? How did I access him? How did we get on? Did he put any money in and why not? What did he think of the film? Did he have any control over the final film?

I answer honestly: I basically snuck in while Kim made his foray into politics in 2014. He had to be relatively public then, taking to the road with Internet Mana, a political mashup of a party that sought to take advantage of New Zealand’s MMP (mixed-member proportional representation) political system. I was persistent, as documentary makers have to be. But it took us several years to get a definitive interview with him and to access his archive. Producer Alex Behse and I knew we would need to make the film regardless of whether Dotcom gave us access or not. From Roger and Me and Waiting for Fidel through to We Steal Secrets: The Story of Wikileaks and the recent Gringo: The Dangerous life of John MacAfee, documentaries structured around the quest or struggle for access are relatively common.

Editorial control had to remain with us, the filmmakers. Kim Dotcom is smart, he knew the film not only had to be independent but had to be seen as independent to have any credibility. We, of course, received no financial support from him.

And in the end I treated Dotcom as I treat all of my main subjects. I showed him the film in late rough cut just before completion, asking first if there are any factual errors and second if there is anything he really hated. In this latter instance I say we can talk or even fight about it, but that the editorial control has to remain with me. In the end there were some minor issues that we battled over and two that were changed in consultation with lawyers: but nothing that I felt compromised the editorial line of the film.

Another set of questions regularly comes up on the film festival circuit: “What is he really like?” In other words, is there an authentic Kim that lies behind these images? Did I find one and was I able to get beneath the surface? I really don’t know. One thing I have picked up anecdotally from audiences is that people’s opinions of him are not radically changed by the film. Those that dislike him going into the film find plenty of evidence to stoke that dislike, and similarly those that might admire him, at least for his hutzpah, feel similarly.

Regardless though, audiences often say that they found him “more human”, which suggests there are moments in the film where Dotcom seems more authentic than others, “glimmers of authenticity” let’s call them. These are generally associated with the moments of emotion which, although brief, appear to stick in audiences’ minds. Anger at a life and business destroyed, sorrow at the collapse of a marriage, reflections on a cruel childhood.

But, most markedly, I think it comes with his apology after the failure of Internet Mana, Dotcom’s ill-fated detour into politics. In the end, New Zealanders, while having some sympathy for him as the underdog attacked by mighty government and corporate forces, rejected his entry into politics. On election night, when it was revealed that Internet Mana faced political oblivion, Kim Dotcom blamed himself, stating “my brand was poison”, and this seems a moment in the film where he exhibits true self-awareness.

But when you think about it, although the moment does feel genuinely heartfelt, and yes, authentic, Kim Dotcom describes himself as a “brand”. Are people, in fact, brands? Do we all always fashion ourselves as brands? Is there life outside brands? This clip and these questions of course take us back to the question of authenticity and the conundrum about selfhood and representation that perhaps none of us, in the film world, or in daily life, ever escape.

Annie Goldson is a Professor of Media and Communication at the University of Auckland.

This article is adapted from her recent keynote address at the 2017 Big Screen Symposium: Authenticity and Pretence. For more information about the film and a bank of ‘extras’ licensed for non-commercial reuse through Creative Commons, visit http://kimdotcom.film/

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author’s views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.